In 1843, Joseph Robidoux founded the city of St. Joseph. On Saturday, one of Robidoux's descendants visited the city to speak about the family's long history.

(ST. JOSEPH, Mo.) In 1843, Joseph Robidoux founded the city of St. Joseph. On Saturday, one of Robidoux's descendants visited the city to speak about the family's long history.

Stephen Kling is a direct descendant of the Robidoux family and the author of "The Battle of St. Louis, the attack on Cahokia, and the American Revolution in the west". The book tells of the attack the British planned on the area of St. Louis in 1780 during the Revolutionary war.

Downtown Abbey event venue invited Kling to speak at one of their 'History Speaks' events. These events focus solely on the untold stories of St. Joseph's history.

"We were elated to have Stephen Kling, author and direct descendant of Joseph Robidoux, come and speak at our little facility, and invite the public," Joni Wescott, co-owner of Downtown Abbey, said.

Click on the link here to see the story - https://www.kq2.com/content/news/Descendant-of-Joseph-Robidoux-Visits-St-Joseph-464698283.html

Courtesy of Stephen Kling

Family Tree Quotes, www.familytreequotes.com

As always, we are looking for new and updated information on the big ole Robidoux Family! If your on our master mailing list, don't forget to update us with a change of address or phone number if you move! Cousin Clyde Rabideau is always on the look out for new info, as am I and so many other cousins doing research! And not to forget, there are numerous spelling variations on the name, so if your not sure if your a Robidoux, send us an email!i

Tks

Kim

**NEWS** **NEWS** **NEWS** **NEWS** **NEWS** **NEWS** **NEWS**

Official opening of the Louis Rubidoux Library in Rubidoux, California, April 2010. . .

Cousin Joe Rubidoux

On Facebook? RANA now has a facebook page. Feel free to log on and chat with cousins from all over the US, Canada and France!

Kim

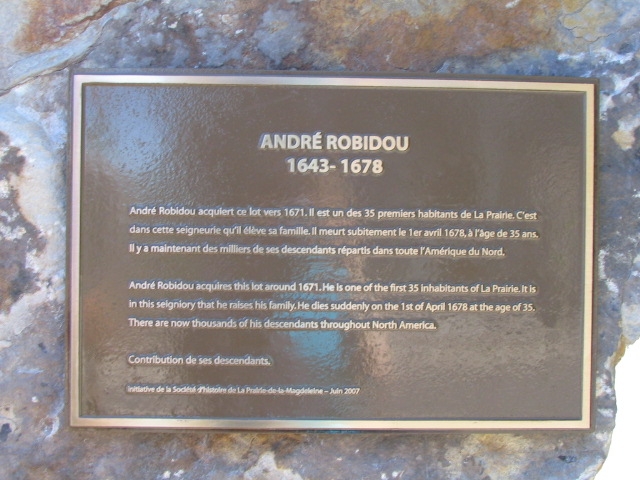

On September 6th, 2009, the offical unveiling of the dedication of a plaque in commeration of our ancestor, Andre Robidou dit L'Espagnol, took place in LaPrairie. The event was attended by over fifty people, including cousins from as far away as California and New Jersey and New York. Many thanks to everyone who took the time to attend. Thanks also to cousin Clyde Rabideau, who was the impetuous behind the idea of a dedication plaque.

Those interested in wanting to visit on your own, here are the directions courtesy of Andre Robidoux: 220 Saint-Ignace street in the old La Prairie, south of Montréal city. You can get there by road 132 or hightway 30. From that highway 30, you have to take the only exit that leads to La prairie (road 104 ou St-Jean boulevard). That road will take you straight to Saint-Ignace street. You have to pass in front of the only church (La Nativité) of old La Prairie. Then, turn left on St-Ignace and stop at about 100 feet from the corner. The plaque will be on your left side, fixed on a piece of rock about 6 foot high: you cant miss it!

Everyman is a quotation from all his ancestors. Ralph Waldo Emerson

Filles Du Roi

With so much focus on our ancestor, Andre Robidou dit L'Espagnol, we tend to forget that his role in populating Canada and the United States was not something he managed on his own! The sheer tenacity of the women who came to Canada, these Filles du Roi, who left everything familar to them to come to a strange country to marry men they did not know, to endure the hardships of settling in a new country, are only a few of the reasons they deserve our admiration and respect. Our founding ancestor, Andre, was lucky enough to have met and married such a Fille du Roi, Jeanne Denote. Her name is recorded in the annals of these women: Denot, Jeanne, m. 1. Robidou, André, Jun. 7, 1667, m. 2. Surprenant, Jacques, dit Sanssoucy, Aug. 16, 1678. (see the website listed below www.fillesduroi for further info)

Kim

The Filles du Roi, or King's Daughters, were women shipped to New France under royal auspices in the mid-seventeenth century to rectify an imbalance of the sexes in the colony of New France(1).

From 1608 to 1663, the colony of New France had been under the administration of commercial companies, formed by merchants from various cities in France. These companies promised to settle and develop French land in return for exclusive rights to its resources(2).

But colonization led by business meant that economic interests and trade took priority. The population was mostly men: traders, storekeepers, workmen, indentured servants, dockhands, soldiers, seamen and clerics. Bringing wives and children meant more mouths to feed. Family members weren't all able to contribute for the profit of the colony.

As a result, these French companies failed to achieve the desired results of establishing a colony of settlers. In 1663, after half a century of occupation, only one percent of the land claimed by France was being used and the population of New France numbered scarcely 3,000, 1,175 of whom were Canadian born. British colonies at this time had expanded to 100,000(3).

In an attempt to increase the fortunes and families of the colony, the impotent company rule of New France was replaced by a royal government. The young monarch, King Louis XIV, initiated a new French era in Canada with an aggressive immigration policy and incentives to encourage marriage and child bearing. One of his strategies was to even out the imbalance of the male and female populations by sending to New France what has become known as the "King's Daughters," or "les filles du roi"(4).

The King's Daughters were women of marriageable age who were sent to New France at state expense as wards of the King between 1663 an 1673. An estimated eight-hundred to one thousand girls arrived during the first 10 years of the royal government and were commonly referred to as "les filles du roi." They were brought under the careful supervision of various authorities such as the clergy. These women brought trousseaus and in some cases, were supplied with a small dowry if they could not afford their own. Some were Parisian beggars and orphans. Others were recruited from the La Rochelle and Rouen areas. Administrators' reports suggest that many were ill prepared for the arduous life of the Canadian peasant(5).

Quick marriages and families were encouraged. Almost all of the King's Daughters found husbands quickly. Further incentives to procreate were given in money grants to young married men and fathers of large families. Annual gratuities of up to 400 livres were rewarded to families of 12. Bachelors were penalized; hunting and fur- trading privileges were withheld to encourage them to settle down and start a family. Marriages between French and aboriginals were also encouraged. It was an active campaign supporting family values and it reaped the desired results. When the offspring of the "filles du roi" came of age 20 years later, the demographic situation of New France had indeed changed(6).

In 1663 there had been one woman to every 6 men; now the sexes were roughly equal in number. By 1671, there had been 700 births. During the first decade of royal government, in fact, population climbed to over 9,000. From then on, immigration fell away, largely due to declining government aid as France became caught up in costly new wars in Europe. Nevertheless, the tradition of large French- Canadian families was now well established. The still-growing colony went on replacing over ninety percent of its people through natural birth, rather than immigration(7).

http://www.whitepinepictures.com

For further reading see also, The Kings Daughters - http://www.fillesduroi.org